- posted: Dec. 29, 2020

- Community Involvement, Outside General Counsel, Firm News

I am sharing the following story for younger professionals who desire to work on projects that make a significant, positive societal impact. I hope you can look back on your career satisfied with what you did to help where and when you could.

When I was a young lawyer at Brown, Vlassis & Bain, P.C. in the early 1970s, one of the firm’s clients that excited me the most was the Navajo Nation. The engagement of Brown, Vlassis & Bain signaled the first time the Navajo Nation had retained outside lawyers to serve as General Counsel. There was so much work to do in a variety of areas. My assignments primarily focused on the creation of the Office of Navajo Labor Relations (which still exists today) and negotiation of the labor and employment matters for the Navajo Generating Station located near Page, Arizona. My work on these projects started during my first year of legal practice and lasted until 1975.

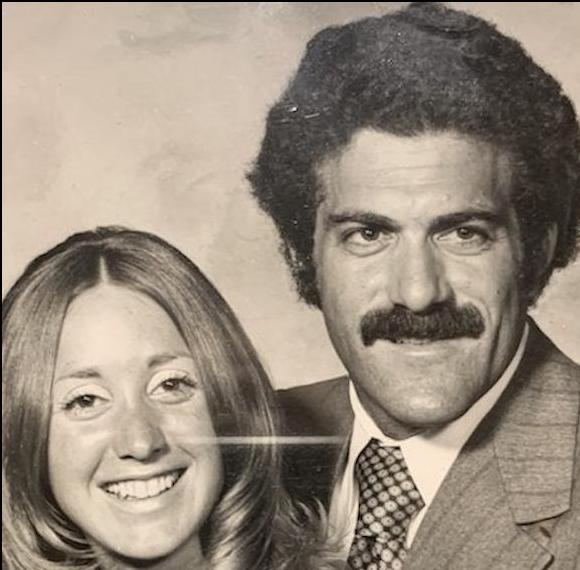

In those days, I had a mustache and a huge Afro—a look I maintained throughout the negotiations relating to the construction and operation of the Navajo Generating Station. I am sure the look was off-putting to the old-fashioned leadership of the Salt River Project (SRP) and Arizona Public Service (APS)—the two entities involved in establishing the coal-fed power plant, and two of most important businesses in Arizona at the time.

A component of establishing the Office of Navajo Labor Relations was interviewing and hiring the Office’s first Executive Director. After many unsuccessful interviews with less than compelling candidates, we were fortunate to find and hire Tom Brose, who proved to be a greater leader as the first Executive Director.

The hiring processes for construction and operational positions at the Navajo Generating Station highlighted the bigotry of the time. Many contracting and utility company executives said they could not find competent, “qualified” Navajo workers. Of course, this was not actually the case. To combat this embedded prejudice, we bypassed the option of “affirmative action” in our hiring processes, and instead employed a program of "preferential hiring"—a policy agreed to by an employer to hire qualified union members. Given the Navajo Nation's significant pre-existing coal industry, the contractors and utility companies unsurprisingly ended up finding Navajo workers who fit the bill. This policy of preferential hiring went on for roughly 45 years, helping to combat otherwise pervasive discriminatory hiring practices and contributing to the employment and promotion of thousands of Navajos to well-paying jobs during this period.

When we were wrapping up negotiations on the Navajo Generating Station, my young associate attorney friend from Northwestern University Law School, who was then with Snell & Wilmer, called me from his small office and said he was there with the heads of SRP and APS. I could imagine the scene. The two big guys in town and my young buddy from law school. I said, “What’s the problem?” My friend said, “They believe that you had been unreasonable in the negotiations.” That, of course, made me feel really good. I said, “Oh yes, what’s an example?” He said, “You said that you want them to post all of the deal terms in Navajo on all of the gates into the power plant during construction and thereafter.” I said, “What’s wrong with that?” He said, “There’s no Navajo written language.” I thought for a moment, laughed to myself, and said, “Yes, I guess that is unreasonable. We can dispense with that requirement. The deal terms can just be written in English.”

I kept asking for more and more money for an assortment of initiatives. To my surprise, SRP and APS kept saying, “Yes.” I thought I was a tremendous negotiator. In reality, their acquiescence to my requests was a function of their ability to use these add-on items to justify charging higher rates to Arizona users. So SRP and APS were more than happy to meet my demands, including a $5 million management training program for the Navajos who lead the Generating Station.

All these memories came rushing back recently after reading the press coverage chronicling the decision to cease operations and decommission the Navajo Generating Station. It hit me that I lived long enough to see the station's planning, construction, decades of operation, and demolition. My son, Keith Galbut, who was just an infant at the time, is now an experienced partner with Galbut Beabeau. How time flies.

Reflecting on the work I did for the Navajo Generating Station drums up bittersweet feelings. While the station created lots of economic benefits for the Navajo Nation, including thousands of well-paying jobs, and built up the City of Page, Arizona, it was also a major air polluter over the years. Unfortunately, we were not nearly as aware of the environmental problems with coal power plants during the Generating Station's planning and development as we are today.

My experiences negotiating with SRP and APS on behalf of the Navajo Nation reinforced in me the importance of zealously advocating for my client’s best interests and leaving no stone unturned in searching out auxiliary avenues for added value. While the practice of law has changed since these formative experiences, the ability to make a lasting impact on a client matter, regardless of seniority, has not. I encourage young lawyers and other professionals to welcome client matters of significance and challenge, particularly when the outcome can better society and our community. These opportunities to create positive change remain some of the most satisfying projects of my career. I hope you will find similar fulfillment in your professional endeavors.